Minerals: Finland’s next Nokia?

Summary

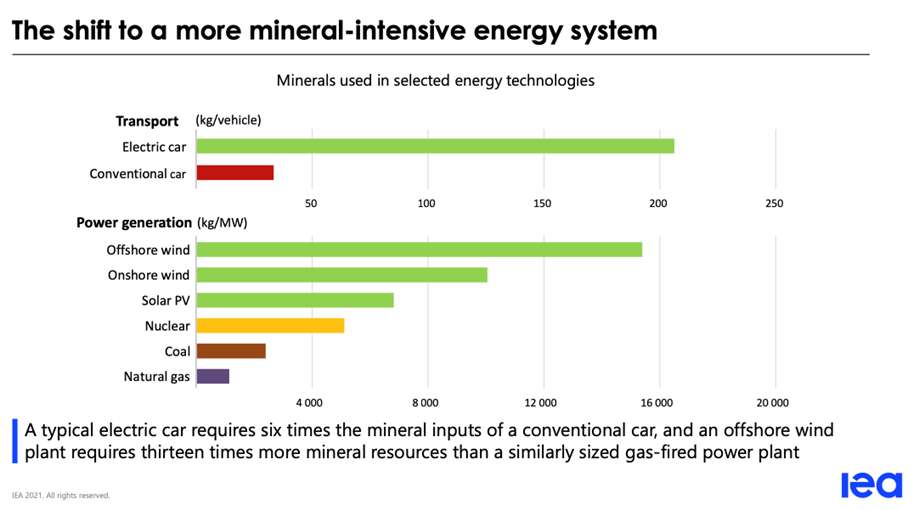

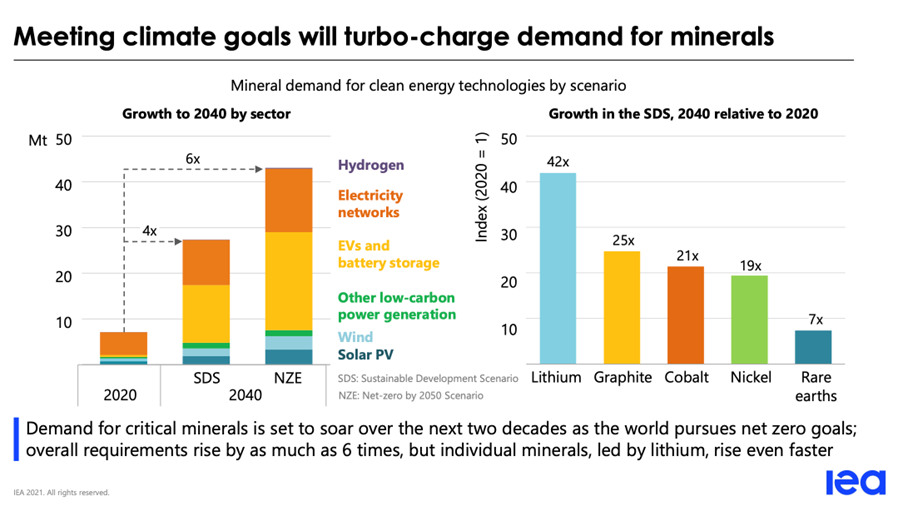

- The global race is on for industrial raw materials, including metals. Materials are needed for high-tech equipment, batteries, cars, and various consumer goods. The green transition is dramatically increasing the demand for metals and minerals, driving competition for rare raw materials.

- China dominates the global trade in metals and minerals. COVID-19 disrupted global production chains, and the chaos was further exacerbated by Russia’s attack on Ukraine. In these difficult circumstances, Finland is extremely well positioned to emerge as winner.

- Latitude 66 Cobalt is a key player in the Finnish mineral extraction industry. The company is exploring the opportunities of extracting cobalt in north-eastern Finland and eastern Lapland. Here to answer our questions is the CEO of the company Thomas Hoyer.

Thomas Hoyer, how would you describe the current global market for high-tech metals? What are the critical metal raw materials?

Critical materials at present are energy transition minerals, in other words raw materials vital for the green transition. These include lithium, nickel and cobalt used in batteries, plus rare earth elements (REE) critical in wind power and copper needed in expanding the electric grid.

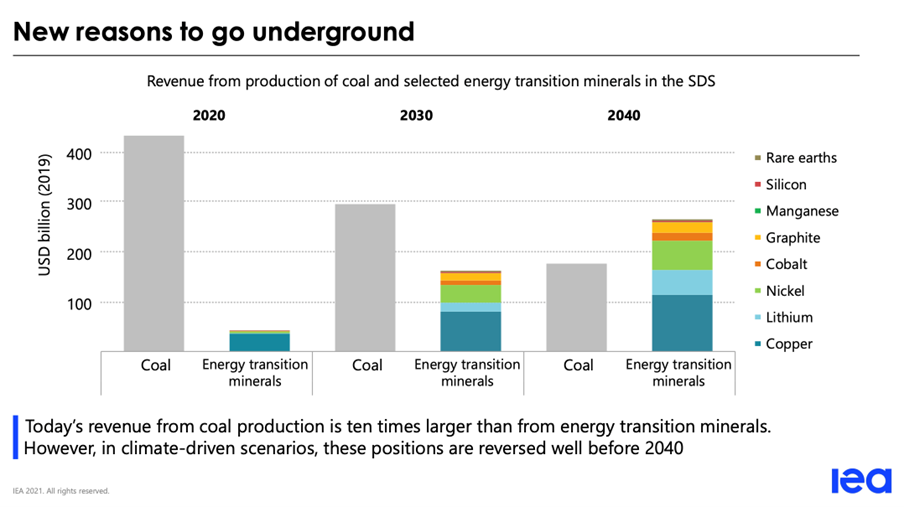

A recent report by the International Energy Agency (IEA), which compared coal mining revenue with that from green transition minerals, provides an accurate illustration of the development. In 2020, revenue from coal production was ten times higher than from green transition minerals, but by 2030 it will be double, and by 2040, ‘green minerals’ will have clearly outperformed the carbon sector.

The nature of the mining industry will change dramatically in the near future. Today we extract material for disposable goods, but in the future mines will provide the foundation for electricity generation, that is, to produce materials that will primarily be used for the transmission and storage of electricity. Naturally, these materials will be recycled and reused much more efficiently than they are now.

What role will China play in the global trade in critical metals? How dependent are we on China?

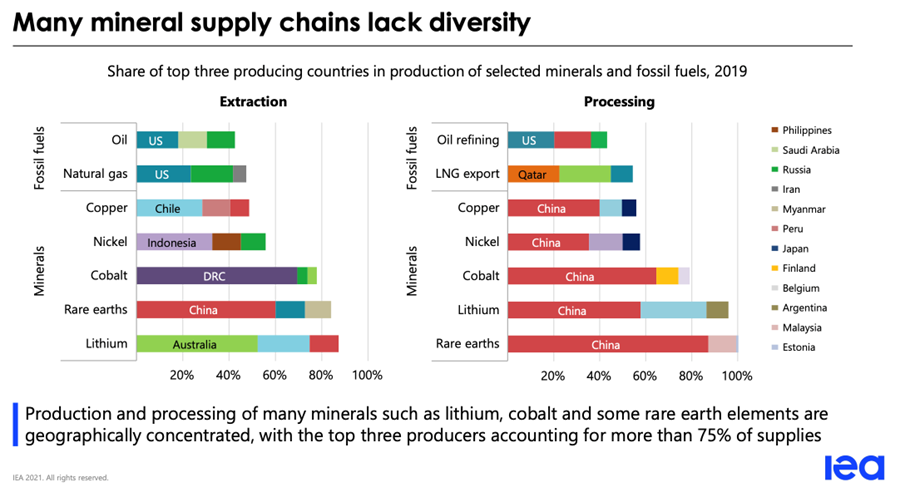

China has been quicker than other countries to understand that battery minerals will be in short supply. Their strategy has been to build dominating processing capacity, which will allow them to process raw materials at such a low cost that it’s not viable for anyone else.

Graphite is a case in point. It is in relatively high supply, and while only about 50 per cent is produced in China, it is processed for battery purposes almost exclusively in China.

As a cobalt processor, China holds a 70 per cent market share. Finland comes second with a share of 15 per cent. We process cobalt in Kokkola, Harjavalta and Sotkamo.

China doesn’t play by the same rules as its competitors. In China, you don’t go to a bank and ask for a loan; instead, decisions are made in Beijing and communicated to the selected two or three state-owned companies. This significantly affects the normal price mechanism and forces competitors out of the market. The market for cobalt, for instance, was intense but our Kokkola processing plant recorded a loss as a direct consequence of China controlling the prices.

The largest known reserves of rare earth elements are in China (38%, 44 Mt), Vietnam (19%), Brazil (18%) and Russia (10%). How does this affect the strategic success products of Finland or Europe?

There are 17 rare earth elements in total, and they can be found in Finland. We can produce a basic concentrate that usually contains several of these 17 REEs. But the fact is that practically no other country except China can separate these elements from mined ore. There was a facility in the United States, but it went bankrupt and – what a surprise – the Chinese bought it.

The most important rare earth elements include neodymium, dysprosium and praseodymium. The power to weight ratio of magnets made from these materials is superior to ferrite magnets, which makes them a valuable building block for wind turbines in particular. More than 1000 kilograms is required to build a five-megawatt power plant, and the sole supplier is China. Rare earth elements play a major role in the manufacture of equipment such as interceptor aircraft, which gives the whole thing a direct defence policy angle.

Going forward, which metal will be the most critical commodity in global trade?

Copper, without a question. Copper is the new oil.

The transition from centralised to more decentralised energy generation involves replacing the existing transmission networks. There is also going to be a huge need for conductivity, and of all materials, copper offers the best properties when it comes to conducting electricity. Every wind turbine, every charging station and every solar panel is fitted with copper cables.

The media is keen to report on the demand for raw materials but tends to ignore the supply side. The world’s biggest copper producer Chile is currently seeing a dramatic drop in the average copper concentration in ore. This means all the good material has already been extracted, and we are facing long-term demand growth.

If the average concentration halves, the amount of ore needed to produce the same amount of copper doubles. This means the costs are doubled, and the environmental footprint is larger.

The United States has announced its intention to challenge China in raw materials, but it is going to take some time?

Sure, but I like the American way of thinking. They say “The Chinese have taken over the markets, it’s high time we did something”, whereas in Europe politicians say “The Chinese have taken over the markets, there’s nothing we can do about it.”

President Biden invoked the Defense Production Act to increase the output of cobalt, lithium and nickel – the same thing President Trump did for ventilators when the COVID-19 pandemic began. What this means for minerals is the fast tracking of permit procedures, for example. In the extraction industry, this was seen as a huge symbolic gesture.

During the administration of both Trump and Biden, the United States has clearly stated that is has close allies in Canada, Latin America, and Australia, and that it wants to secure the supply of critical raw materials. Although the United States, unlike China, has no state-owned companies, it is customary for private companies to sign very lucrative long-term contracts with the Department of Defense, or the Pentagon.

Canada has invested two billion dollars in a special fund to guarantee the supply of critical raw materials to Canadian industry. In Australia, a state-owned investment company recently made a major investment in a mining development company – in effect, in nickel and cobalt production. The global race for raw materials is clearly on.

What can Europe do to improve its position in the raw materials market?

We have been blind in Europe. We have simply been happy that China buys and sells. We’ve laughed at geopolitics and chanted the just in time mantra, convincing ourselves that it makes no sense to stockpile anything and that we should buy the cheapest. We gladly outsourced ‘dirty industry’ to China.

Germany has made moves to secure access to critical raw materials. For this, it used the Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau, a credit institution established to finance the reconstruction of East Germany. The way it works is that a mine in a friendly country enters into an agreement to sell the necessary quantity of its output to a German customer, and in return the KfW provides credit on affordable terms.

The UK is no longer restricted by EU regulations. They have always been very competent when it comes to foreign policy, and I believe that British industry will come up with its own solutions.

What role do consumers play here?

A very big one.

It would be naïve to think that China only wants to control the electric vehicle battery market and not expand to making electric vehicles. This is where European consumers can step up. I believe the buyers of electric cars want to know more about their cars than just the power output or driving range.

On page four of the brochure of my electric BMW, it says: ‘We know the origin of our nickel and cobalt’. Metals used in vehicle manufacture can be traced, and manufacturers can promise that they have not used unethically mined cobalt from the Democratic Republic of Congo.

If you are a smart manufacturer, this is how you prepare for future competition. BMW, for instance, has signed an agreement with mines in Morocco and Australia to buy cobalt concentrate and pay the processing margin up to the end product. Tesla has announced that it is prepared to buy a lithium mine.

This may be an option for a German auto giant, but what are the choices for a small manufacturer unable to sign a similar agreement?

They are naturally more at the mercy of China. Finnish companies can try to buy cobalt from Kokkola and Harjavalta, if sufficient raw material is available.

Russia has vast natural resources. How will Russia’s attack on Ukraine and the resulting sanctions affect the global extractives trade?

Nickel is the biggest problem. Problems are also to be expected with the production of palladium and platinum, especially palladium.

The Russian invasion seriously disrupted the nickel market. The Russian Nornickel is one of the world’s biggest refined nickel producers. There are huge Chinese-funded nickel mines in Indonesia and the Philippines, but the problem is that much of the nickel available globally is not suitable for making batteries. Meanwhile in Talvivaara in Finland, the concentration is low, but the nickel is suitable for batteries.

Overall, I would say we will be able to live with the sanctions imposed against Russia and things will remain on track, unless China invades Taiwan. If the West attempts to impose similar economic sanctions on China, as it did on Russia, the manufacture of batteries, cars and many other things will stop pretty quickly.

How large are Finland’s cobalt reserves and how easy are they to utilise?

While it has been a known fact that there is cobalt in Finland, it wasn’t until recently that determined exploration began. The Geological Survey of Finland conducted a survey of the largest known cobalt reserves in Europe and found that the four largest deposits are in Finland, the next biggest are in Sweden and Spain, then another three deposits are in Finland. The deposits found in Finland were clearly the best, not only in terms of quantity but also by concentration.

But the best news is that we have no need to ship cobalt to the other side of the world, because 15 per cent of the global processing capacity is located here. Idaho in the United States is geologically similar to Finland, but when cobalt is found there, the only place to sell it to would be China. And that’s no small matter, considering the current problems with cargo transport and container shortage. In Finland, there is no need for containers. From Posio, it’s only 250 kilometres by road to the nearest processing facility.

Copper, nickel and lithium are also found in Finland. There are nickel refineries in Harjavalta and Talvivaara. We have a long tradition in copper production, although there have been problems with the availability of domestic raw material.

Environmental issues have given the mining industry a bad name. What are the implications?

Big mistakes were made at the Talvivaara mine, which affected the reputation of the entire mining industry. But we should bear in mind that there was a time when people were strongly against the forest industry.

Possibly sentiments on mining differ quite a bit depending on where you live. On the west coast people accept that industry needs raw materials, and that recycling is not the answer to everything. On the coastal strip from Haaparanta to Uusikaupunki, communities rely heavily on metal processing, as it provides 120,000 direct and indirect jobs.

What do you expect from politicians or the government, or the next government programme?

Many countries recognise the concept of a ‘project of national interest’. Perhaps we should advocate this line of thinking.

Emma Kari, a representative of the Green League, suggested that green transition projects should be placed first in line. This is a good idea. I hope that these include projects that enable the transition; not just wind turbines themselves but the entire material supply chain and production chain that are necessary for their construction. I’m not advocating loosening the permit procedures, but that there should be some prioritisation.

If successful, how would the cobalt cluster affect the Finnish economy?

Finland is in a unique position in that we have significant cobalt resources, and we have the technology to extract it ethically and responsibly, allowing us to create a minimal environmental footprint. We have cutting-edge mining technology companies such as Metso and Outotec. And, as I said earlier, we have the skills and the facilities required for cobalt processing.

As we transition away from internal combustion engines, it’s not just passenger vehicles that will be affected. There will be a vast number of applications around lithium batteries, with the automotive industry representing just a small part. Here, Finland could play a role as a technology hub.

Attracting Tesla production to Finland should be our goal, because we have the know-how and the raw materials needed. We should be able to convince car makers to set up operations here by promising them there will be no shortage of materials. That’s what many other countries do.

Text Matti Apunen